Colorado lawmakers approved $30 million in rental assistance on Monday during a special legislative session in an effort keep more people in their homes as eviction filings in parts of Colorado hit record high numbers.

As of Monday, there had been 34,757 eviction filings this year across Colorado, up 9% from the 31,920 filings in the same period in 2022.

Recent data from Denver County Court shows the city has logged a record 10,849 evictions, surpassing the 10,241 reported in 2010 in the depths of the Great Recession.

But research suggests for every eviction there are two other households that self-evict early on in the process before they’re formally removed from their home by a local sheriff.

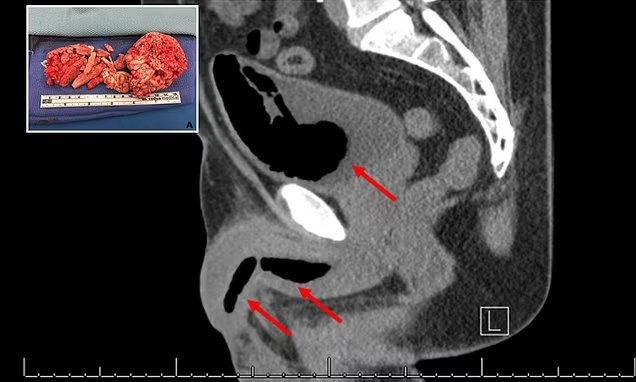

That’s how it went for Elizabeth Chambers, an Aurora mother of four, who had been complaining for four months to her landlord about problems including a cockroach infestation, broken windows, exposed wiring and a malfunctioning heating system.

When her work hours decreased, it became harder for Chambers to pay the $1,575 she owed each month for rent.

In August, Chambers couldn’t afford to pay the full amount of rent and her landlord quickly filed eviction papers.

To preserve her credit, Chambers went to Arapahoe County Court and agreed to move out before the formal eviction was granted.

In Colorado, if a person moves out of their home before an eviction judgment and follows the proper court process, the record is sealed and won’t end up in a landlord or tenant database, where landlords go to conduct background checks before they offer someone housing.

She found a new apartment in Aurora, but lived in her car with her kids for about three weeks until the previous tenants moved out. “It was a mess but I was thankful to have shelter,” Chambers said last week.

New funds to help curb Colorado evictions

The $30 million in emergency rental assistance approved by the legislature is intended for households earning up to 80% of their area’s median income. To qualify, renters have to be able to show financial hardship that puts them at risk of eviction.

Any money that isn’t distributed to landlords before July 1 will be sent back to state coffers to spend on other programs.

“We’ve heard loud and clear from voters and from Coloradans that the housing crisis and the rising cost of living has really, deeply impacted families,” said Sen. Julie Gonzales,a prime sponsor of the bill with Rep. Leslie Herod. Both are Denver Democrats.

“The special session was convened to address property tax relief but was also convened to keep Coloradans housed,” Gonzales said Monday afternoon, after the four-day special session ended. “I think there’s a strong argument that we could have done more, but given the limited tools that we had and given the limited time that we had, I’m really proud that we were able to get $30 million to be utilized between now and the end of the fiscal year in June 2024.”

In Denver, in October alone, there were 1,629 eviction filings, the highest number of any month this year, according to the data. The second highest number of eviction filings were in May when 1,216 cases were counted, according to the court data.

Since 2021, each year in October, eviction filings have approximately doubled in Denver, according to the data.

“It’s really simple. Rents have gone up dramatically and the accessibility of rental assistance or other financial assistance programs has decreased dramatically,” said Zach Neumann, executive director of the Community Economic Defense Project.

The 2020 COVID-19 relief bill included $25 billion in emergency rental assistance and the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021 provided almost $22 billion for the same cause. In all, the programs provided almost $47 billion in emergency rental assistance and housing stability services nationwide.

Several Colorado counties and the state were collectively allocated more than $700 million in rental assistance through the COVID-19 relief bill and the American Rescue Plan Act.

“Almost all of that money has been used,” Neumann said. “And now most folks are depending on the few remaining dollars in those programs or much smaller state and local programs.”

Dozens of tenants and residents, joined by Colorado Homes for All, gather with signs opposing the Apartment Association of Metro Denver June 22 in Playa del Carmen Park. Demonstrators held an anti-award ceremony, dubbed the “Slummy Awards”, in which a “Corporate Greed” character was awarded for practices that disadvantage those who are currently living with unmet housing needs. (Olivia Sun, The Colorado Sun via Report for America)

Dozens of tenants and residents, joined by Colorado Homes for All, gather with signs opposing the Apartment Association of Metro Denver June 22 in Playa del Carmen Park. Demonstrators held an anti-award ceremony, dubbed the “Slummy Awards”, in which a “Corporate Greed” character was awarded for practices that disadvantage those who are currently living with unmet housing needs. (Olivia Sun, The Colorado Sun via Report for America)

For the first time in 20 years, the average American is rent burdened, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing, he said.

“All of the economic research shows that is unsustainable,” Neumann added. “It means that a single financial emergency can result in not being able to pay rent because people literally have no margin at all. So if you miss a shift, if you have a flat tire, if you get towed, if you have an unexpected doctor’s visit, those are all things you have to pay for and you certainly don’t have enough money to pay rent.”

Eviction or displacement from housing is associated with severe consequences such as physical and mental health decline and difficulty finding or retaining a job, he said.

Children often struggle in school after an eviction. Children under 5 years old make up the largest group of Americans whose households have had an eviction filed against them. About a quarter of Black babies and toddlers in rental households face evictions each year, according to PNAS, a scientific journal.

Reliance on emergency rooms goes up for people after evictions, risk of incarceration can increase and so can rates of addiction, Neumann said.

Generally, for landlords, evictions are associated with unpaid debts that are hard to recover, he added.

“A lot of what we’re talking about here are eviction filings, which is just one piece of a much larger puzzle of forced displacement,” said Jacob Haas, senior research specialist at The Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

“There’s a heck of a lot happening outside of the formal court system, in terms of families being forced to move from their houses, whether that’s a cash for keys kind of arrangement or whether that’s an illegal lockout,” he said.

Denver kicks in $22.1M in rental assistance, but is it enough?

It’s alarming to see increasing numbers of eviction filings across the state, Neumann said, but it’s encouraging to see that Denver approved, earlier this month, about $29.1 million in emergency rental assistance to help Denverites facing eviction next year.

The rental assistance fund has been available for years. But this is the first time the city council banded together with all 13 city council members supporting amending the mayor’s budget to help ensure there was adequate funding to help people facing eviction in 2024, said Shontel Lewis, one of the council members who worked to find the additional funding. Mayor Mike Johnston opened budget negotiations with $12.6 million in rental assistance.

Members of the city council and the mayor’s budget office found the additional money in savings across city agencies, in a fund that would have been used for graffiti removal, and in a pool of money intended for property tax relief that is larger than the anticipated need in 2024, councilor Sarah Parady said.

Lewis said the $29.1 million budgeted will likely prevent only about half of the eviction filings expected in 2024.

During the supplemental budget process in mid-2024, the city council will review the budget and decide whether more money should be made available for rental assistance, Lewis said.

Lewis encouraged people in Denver to identify the top needs in the city and to decide whether those priorities are reflected in the city budget. “Budgets are moral documents and this is a really good opportunity for folks to look at our budget and really check our morality to see if it’s aligned with where we should be going in terms of the needs within communities,” she said.

Johnston, at a Nov. 14 event celebrating the extra funding, said the spending “is the moral thing to do and it’s the right financial thing for the city to do.”

Currently, if a person is facing eviction, it will cost the city about $5,000 to help them stay housed, he said. If the person loses their home and then becomes homeless, the city will spend about $40,000 to get the person adequate services, Johnston said.

At the event, city council members urged the state legislature to invest at least the same amount of money or more to help curb evictions statewide.

Meanwhile, the Denver mayor’s office is focused on expanding the number of deed-restricted, or permanently affordable units, in the city. In these kinds of homes, a resident would never pay more than 30% of their income on rent. The price for rent would also never increase unless the resident’s income increased, the mayor said last week.

The Denver Temporary Rent and Utility Assistance Program ran out of money in October, and since then, many community members have been contacting Lewis’ office for help to remain in their homes, she said.

Applications for Denver’s rent and utility assistance programs will reopen in January, according to the city website.

The Colorado Senate as a special legislative session on property tax and other financial relief wraps up on Monday, Nov. 20, 2023. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

The Colorado Senate as a special legislative session on property tax and other financial relief wraps up on Monday, Nov. 20, 2023. (Jesse Paul, The Colorado Sun)

Increased need for rental assistance

This year, the Colorado Economic Defense Project’s court clinic has seen increased need from people facing evictions and those who need help with finding rental assistance.

Some weeks, 90 people show up to the clinic, which is unprecedented, Neumann said. “In 2020 and 2021, we were seeing a half to a third of the numbers we’re seeing today.”

Emergency rental assistance is a powerful tool to help people facing eviction, Neumann said. “But it’s not the only thing we should be doing.”

State leaders should make the eviction process harder and longer for landlords because the consequences are so severe, he said.

Currently, a landlord can evict a resident for “an incredibly small” amount of rent owed, he said. “We see a lot of activity around displacement because of nonrenewal of leases,” he said.

Research shows, most landlords rarely evict their tenants — if ever — even in neighborhoods with high eviction rates. According to the research, a small number of landlords evict a high number of residents each year, according to the Eviction Lab.

As long as a person is paying rent and following the rules of the building, their lease should be renewed, Neumann added.

“We have to invest in affordable housing. But that’s the work of decades,” he added.

But Denver isn’t doing enough to build affordable housing that is safe and habitable, Denver Auditor Timothy O’Brien’s office said in a report issued Nov. 16.

The audit examined how the Department of Housing Stability provides oversight of its agreement with the Denver Housing Authority and how it ensures existing housing units are maintained, according to the audit report released last week.

Because of the Department of Housing Stability’s lack of oversight, a program to build more affordable housing isn’t delivering the required number of units needed and, as a result, costs to build could be significantly higher, according to the audit.

Under the direction of the city, the Denver Housing Authority has developed 32 fewer units for “very low-income households” and 301 fewer units for moderate-income households than required by the contract agreement, according to the audit report.

The Department of Housing Stability disagreed with the auditor’s recommendations for improving how the housing organization checks for maintenance, safety and sanitation of its affordable units, the audit report says.

“We observed issues at 14 of 21 properties, despite recent inspection forms from the city showing no issues at these same properties,” the audit says. “Issues included human or pet waste, broken windows, and evidence of pest infestations.”

Another plea for more affordable housing

Before Chambers moved out of her apartment in August, her landlord gave her a packet of resources to help her find rental assistance.

“I wrote down a list of 40 to 50 different places and phone numbers that didn’t have funding or didn’t exist anymore or didn’t serve Aurora residents,” Chambers said. “It was extremely frustrating and it was affecting my work, even, because I wasn’t really working. I was trying to find some place to live.”

Eventually, she got help from Caruso Family Charities in Lakewood, which agreed to send two months of rent or $4,000 to Chambers’ new apartment complex.

The rental assistance was a relief, Chambers said, but she will still be short about $600 when the December rent is due. It’s a never-ending cycle, she said.“We can’t let this level of displacement and suffering continue,” Neumann added. “For the next 10 years, we really need to change law and policy to make it very, very difficult to evict people and to provide financial resources when they are being evicted. I think that’s the approach.”

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·