Robbie LeValley sees her family’s cattle ranch settled in the high pastures near Hotchkiss as a linchpin in the state’s food chain and a fifth-generation steward of the local environment.

The LeValley ranch is bordered by habitat for the Gunnison sage grouse, a ground-dwelling bird that is protected as an endangered species. Grazing has helped the sage grouse thrive and meet recovery goals set by the Endangered Species Act, the LeValleys say.

The water supply for the LeValleys’ public land allotment also originates on their private land. The family has built 17 miles of pipeline, allowing the water to flow from their spread to ponds that are open to the public. The LeValleys say this allows plenty of water for the fishing ponds and the Gunnison sage grouse to thrive.

All the ranches in that part of the North Fork Valley — many of which were settled over a century ago — share a common interest in sustaining the local environment, Robbie LeValley said.

“Each of the ranchers in their own way have taken on the ethic of improving the land for and making it safe for the sage grouse and wildlife in general,” LeValley said. “Ranchers provide the large open space that wildlife need and require.”

Large ranching operations like the LeValleys’ have been targeted by activists accusing them of contributing to environmental degradation, including contributing to climate change. Research published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS Climate claims that phasing out animal agriculture over the next 15 years would have the same effect as a 68% reduction of carbon dioxide emissions through the year 2100, which it says would limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

“Reducing or eliminating animal agriculture should be at the top of the list of potential climate solutions,” Patrick Brown, a professor emeritus in the department of biochemistry at Stanford University, told Stanford Magazine.

The LeValley Ranch and five other ranches own about 2,000 head of cattle that are raised on clean mountain water, fresh air, Colorado sunshine and green grass, the ranchers say. They are not fed antibiotics, added hormones or animal byproducts, according to the LeValley family.

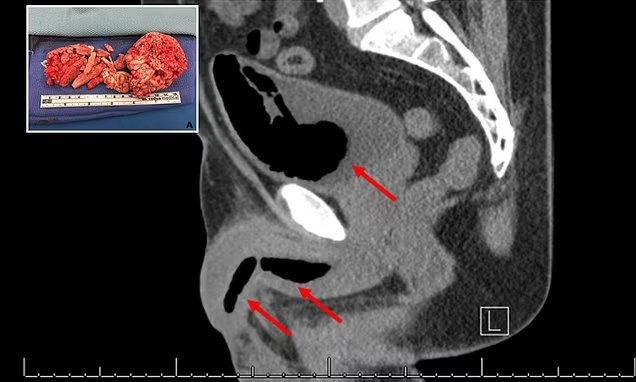

When it’s time to market their meat, the animals are slaughtered and custom processed at Homestead Natural Meats in nearby Delta. That operation is also owned by LeValley and the other ranchers.

The site — including corrals, equipment, flooring, feed and water supply — is regularly inspected by the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, according to the Homestead Meats website.

Farm Runners store employees Lara Widner, left, and Dana Stopher chat while stocking the produce section, Nov. 21, 2023, in Hotchkiss. The store, next to City Market in town, is a year-round regional food distributor for the local farmers and ranchers to Roaring Fork, Gunninson, and Grand Valleys. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

Farm Runners store employees Lara Widner, left, and Dana Stopher chat while stocking the produce section, Nov. 21, 2023, in Hotchkiss. The store, next to City Market in town, is a year-round regional food distributor for the local farmers and ranchers to Roaring Fork, Gunninson, and Grand Valleys. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

A retail store is also on-site where customers can buy beef, pork, lamb and other meats offered by the ranches. Homestead sells Mexican shrimp, tuna and salmon, as well as fresh milk and cheese.

The variety of items tendered to customers local and statewide is the result of the area ranchers deciding in the 1990s to remain viable by catering to changing customer tastes, Robbie LeValley said. The best way to do that, she said, was to open its own processing plant and a retail store where the producers can talk directly to potential buyers.

“Everybody at the time was ranching a cow-calf operation,” LeValley said. “We decided to diversify and add additional processing so we could begin selling directly to consumers. It provides us the opportunity to interact with consumers.”

“It allows us,” she said, “to expand customer knowledge of agriculture in general and what it takes to provide a diversified enterprise.”

The LeValley ranch is roughly 25 miles from its processing plant in Delta. But other grower-owned processors and retailers that allow ranchers to cut out the middleman in Colorado are few and far between. Ranchers often have to travel hundreds of miles to get to a processing facility.

And if an activist group working toward a ballot measure for 2024 gets its way, the lone cooperative processing plant in Denver will be eliminated altogether.

A gaping hole in Colorado’s supply chain

The huge gap between ranchers and processing plants produces a gaping hole in Colorado’s supply chain and threatens the sustainability of meat production, LeValley said.

Colorado is home to 13,000 beef cattle producers and 206 feedlots, all of which are served by 24 USDA certified slaughter plants, according to the Colorado Cattlemen’s Association. Colorado is the fourth-largest exporter of fresh and frozen beef in the United States, with the export market worth over $1 billion, the CCA says.

The meager number of slaughter plants compared to the size of the state’s cattle production is leaving Colorado’s food chain vulnerable to disruption. It also drives up food costs as producers truck their livestock from the far corners of the state to processors on the Front Range while smaller ones are scattered along the Eastern Plains and Western Slope, LeValley said.

“So many of these facilities are just so far out there,” she said. “Depending on the situation, you may have to travel from Fort Collins to Delta for your processing. That is a huge expense.”

“And processing is just a critical part of providing food security for us and the entire world,” LeValley said. “It’s like the energy sector. If one processing center is affected by something, it affects the entire system.”

Homestead’s meat processor Ector Felix cuts off the rib-cage section from half of an 800-pound cow at the facility, Nov. 21, 2023, in Delta. U.S. Senators Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) recently introduced legislation to support small meat processors in Colorado and across the nation that would create grant and loan opportunities through the U.S. Department of Agriculture amid petition drives to shut them down. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)

Homestead’s meat processor Ector Felix cuts off the rib-cage section from half of an 800-pound cow at the facility, Nov. 21, 2023, in Delta. U.S. Senators Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) recently introduced legislation to support small meat processors in Colorado and across the nation that would create grant and loan opportunities through the U.S. Department of Agriculture amid petition drives to shut them down. (Hugh Carey, The Colorado Sun)LeValley is among meat producers who are largely backing a Congressional bid to allow small and midsize meat processing facilities to expand their operations. The “Butcher Block Act” — co-sponsored by Colorado U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet — authorizes USDA loans and loan guarantees to increase and modernize small and medium-size meat-processing and rendering facilities.

The legislation would also develop new mobile facilities to improve local and regional access to processing and rendering services.

Meat industry leaders hailed the proposed legislation for potentially increasing competition among processors and capacity in rural areas. Kent Swisher, president and CEO of the North American Renderers Association, said the bill finally focuses on the importance of recouping the meat, bone and fat from an animal and reusing them for other products.

“This bill is the first of its kind that acknowledges the critical role of rendering as a safe and sustainable method of upcycling the parts of the animal and birds that are not consumed by humans,” Swisher said in a news release.

But the Butcher Block Act runs counter to changing attitudes toward livestock production, a local environmental activist says. Watchdog groups argue that large ranches and slaughterhouses are morally wrong and environmentally disastrous.

Livestock accounts for about 15% of greenhouse gas emissions mainly from methane from the gas they expel, according to Earth First and The World Counts. Large meat operations are also destroying forests and chewing up land for wildlife, the environmental group says.

Huge ranches are guilty of spreading foodborne illnesses while also occupying 30% of the Earth’s land surface leaving less land for other uses, according to Earth First.

Industrial animal agriculture is a key driver of the climate crisis, and replacing it is the necessary part of any climate solution, said Aidan Kankyoku, spokesman for Pro-Animal Future. The group is leading an effort to place a measure on the 2024 ballot to ban slaughterhouses in Denver.

Superior Farms Inc. is the only slaughterhouse in the city and is located in Globeville. The company employs well over 500 people and is one of the largest lamb slaughterhouses in the country, killing over 1,000 lambs daily, Kankyoku said in an email.

“Slaughterhouses dump toxic chemicals into waterways, and most of all, nobody with a heart in their chest can watch the footage of what happens to animals inside these facilities without feeling disgusted,” Kankyoku said.

“New meat alternatives and shifting cultural norms have shown that we don’t need to rely on farming animals to thrive,” he added. “Society is evolving away from a reliance on animal farming, and that’s a good thing.”

Bennet’s bill would be a step backward in the move away from factory farming, Kankyoku said. “There is no place for slaughterhouses in the progressive, peaceful future Colorado voters wish to create,” he said. “The government should be leading a transition away from animal agriculture or, at the very least, stop tilting the scales of competition against humane, sustainable alternatives.”

Superior Farms Inc. could not be reached for comment.

On its website, Superior Farms says it partners with over 1,000 family ranches to provide high-quality lamb with a strong commitment to animal well-being and sustainability.

“The lambs graze mainly on open pasture lands, sustaining on the natural vegetation of vast grasslands as they have for centuries while providing benefits to the land through fertilization, erosion mitigation and wildfire suppression,” the website states.

The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, along with other agriculture groups, has fought against claims that beef producers are a detriment to the environment, noting that beef producers in the United States are already the global leader in sustainable beef production.

The cattlemen’s association said that the industry has committed to climate neutrality of U.S. cattle production by 2040, according to a news release.

LeValley points to work done at Colorado State University as examples of livestock producers working to keep its industry sustainable in an era of changing attitudes toward meat. The Institute for Livestock and the Environment brings in several groups from various disciplines from across the CSU campus to balance issues of “economic growth with the environment,” the CSU website states.

That academic work and research will help determine just how much farms and ranches influence the environment, good and bad, LeValley said.

“So far we’ve only been concentrating on one side of the ledger,” she said. “We’ve been getting the blame for a lot of things without getting credit for what we do everyday.”

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·