In a densely populated Moscow neighborhood intersected by two major highways and surrounded by high-rises is, improbably, a village. Right next to supermarkets, 8-lane roadways, noise and lights stand just over a hundred cottages on quiet tree-lined streets.

It's called the “artists’ village” possibly because the streets are named after famous Russian artists, or possibly because at various times, the sculptor Andrei Faydysh-Krandievsky, artists Pavel Pavlinov and Alexander Gerasimov, director Rolan Bykov and other famous people in the arts lived here.

It was founded in 1923 as an example of the “city-garden” architectural concept by British urban planner Ebenezer Howard, which aimed to combine the best features of living in the city and the countryside. Soviet architects of the time, including the Vesnin brothers, Nikolai Markovnikov and Ivan Kondakov, designed 114 houses. Alexei Shchusev took part in the general planning.

“The ‘artists’ village’ was a kind of scientific and practical testing ground. Houses were created according to the same design, but from different building materials, and using different technologies. Sokol is a rich material for studying the history of Russia, Moscow, Russian architecture, and the construction industry,” Riva Sinayuk, an activist of the social heritage movement Archnadzor, told The Moscow Times.

Later, residents began to upgrade their houses and bring in modern conveniences. In 1979, the area was made a protected landmark area, and each house was protected. Despite the law, in the 1990s, a few houses were torn down and modern mansions built in their place.

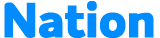

A new mansion on an old plot of land.

Anton Belyaev

A new mansion on an old plot of land.

Anton Belyaev

In 2017, the Ministry of Culture changed the status of Sokol to a “place of interest.” An activist of the social heritage movement Archnadzor, Anastasia Sivitskaya notes that the problem is not so much the status, but “the subject of protection.”

“Sokol was supposed to acquire a high protection status and become an 'ensemble,' (that is, one architectural whole), not a 'place of interest.' We know that Sokol had an object-by-object plan at the level of an official document in Rosokhrankultura. Rosokhrankultura doesn’t exist anymore, and its powers were transferred to the Ministry of Culture. This list has been withdrawn from use as it is not required for the status 'place of interest',” Sivitskaya told The Moscow Times. She said that the status of “place of interest” permits replacing a building with a modern version. This was done at VDNKh and with the old Moskva Hotel. Now the same can be done in Sokol.

Today many people know it as a district in Moscow, not as an “architectural monument.” There are almost no descendants of the original inhabitants. In 2023, Sokol celebrated 100 hundred years from its foundation, but at the end of the year the house designed by the Vesnin brothers, whose constructivist masterpieces are the pride of Moscow and other cites in Russia and the CIS, was torn down. The house was demolished despite the efforts by Archnadzor and some residents. And it was not the only demolition there.

Some residents agree with changes. “When Sokol was a protected landmark area, it was almost impossible to repair houses. Why should I have to get permission for any changes to my house? I pay for it, not the government. I don’t understand my neighbors who protected the house by Vesnin,” a local resident who preferred to be anonymous, told The Moscow Times.

“Vesnin's house had many remarkable characteristics. It was designed by famous architects. It was part of an architectural group of two houses, originally conceived to be the heart of Ulitsa Tropinina. And finally, it was built of Vologda pine that was durable and reliable,” Riva Sinayuk said.

In response to a query, Moscow's Department of Cultural Heritage said that capital repairs of the building were planned, which was permitted by law. But the house was torn down by the owner.

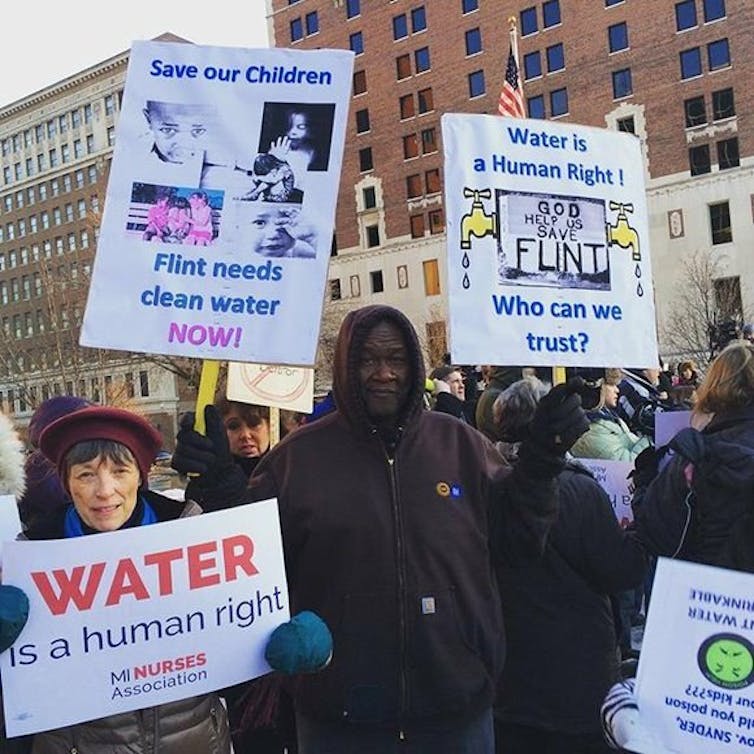

New construction in Sokol

Courtesy of Anton Belyaev

New construction in Sokol

Courtesy of Anton Belyaev

According to Archnadzor statistics, since 2017 they have lost 60 wooden houses, including in Sokol. About 10 buildings survived after restoration. One that is under restoration is the estate of the famous physician Vladimir Snegirev in Moscow, an architectural monument on the federal register. The territory is completely fenced off and the house is under an awning, so no one knows what is being done.

The Dinamo stadium in Moscow is an example of replacement. Built in 1928, it had protected status. But in 2012, its status was changed to a “place of interest.” As a result, it was almost completely rebuilt. But some people supported the decision of the authorities.

“Adapting an old stadium for modern use is a very expensive solution that would only last for the next 5-10 years. Then what? The Dinamo football club is more than 80 years old, and there is no reason to assume that it will not exist for at least as long. Therefore, the stadium is being built with great reserves for the future,” a user named Arkady commented under an article by Archnadzor.

Riva Sinayuk believes that any urban architectural monument that interests a large developer with connections in the government is not protected from demolition or radical reconstruction. The problem can only be solved through the joint efforts of urban protection, the media and civil society.

A striking example of success is the history of the Moscow Church of the Resurrection in Kadashi in Moscow that was saved.

However, while some people try to save historical buildings, others try to make these buildings more comfortable and modern. Is it possible to combine past, present and future? Perhaps. But at present it's hard to tell what most people want.

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·